Foreman’s Branch Bird Observatory

For my “Oh Wow, Warblers” birding course, we had another field trip last week to Foreman’s Branch Bird Observatory in Chestertown, Maryland. Originally founded under the name Chino Farms Banding Station, Foreman’s Branch Bird Observatory (FBBO) has been in operation at its current location since 1998 and is a major migratory bird banding station. Researchers band more birds during migration here than at any other banding station in the country. The station has a rotating team of banders who monitor 92 nets spread over 55 acres each migration season.

FBBO has also forged a long-term relationship with nearby Washington College as a practical laboratory for students interested in field biology, restoration conservation, modern row-crop farming, and the ecological interface between upland Delmarva Peninsula and the Chesapeake Bay.

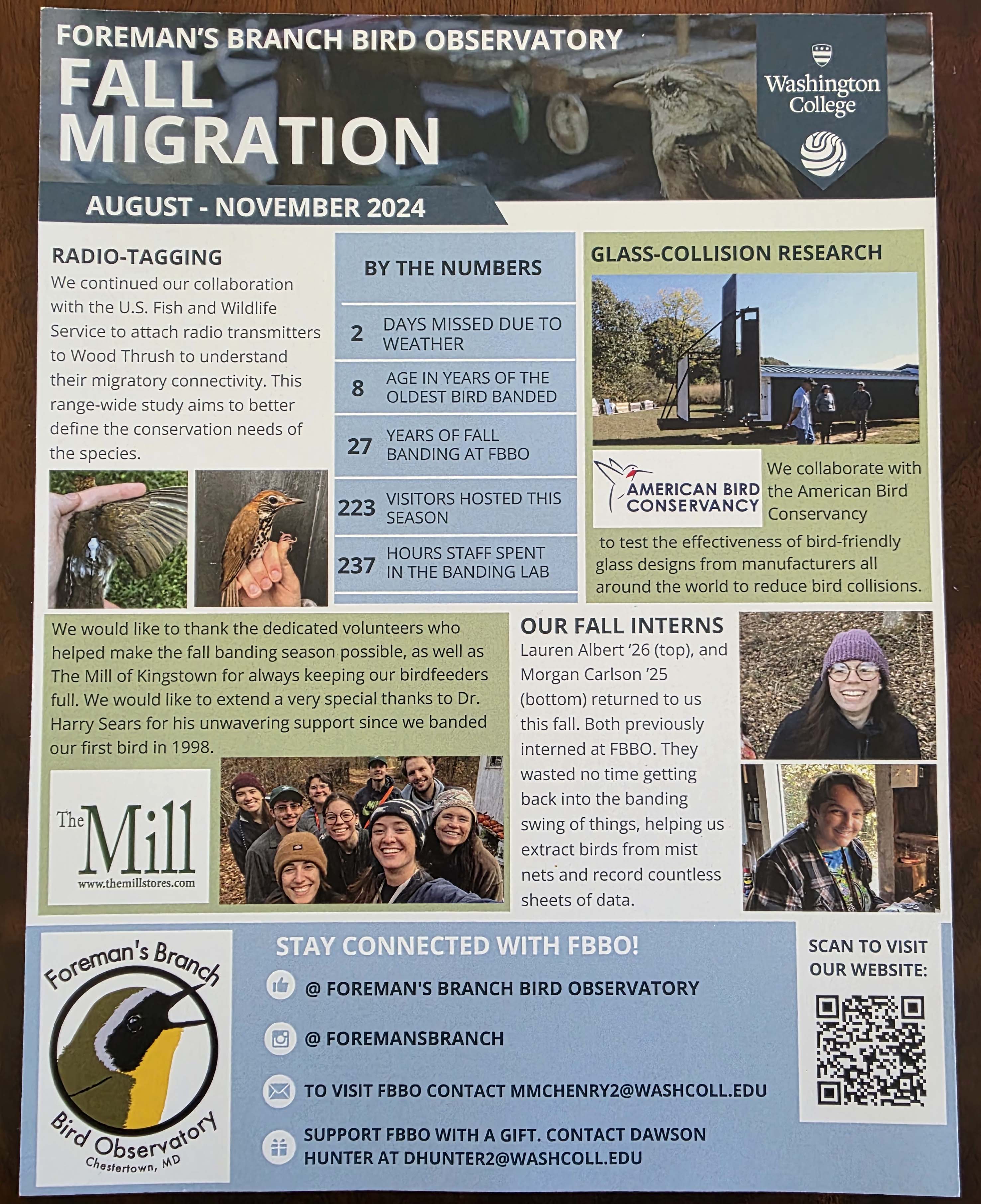

Here’s an impressive two-sided fact sheet for FBBO’s past 2024 fall migration numbers. At the end of the post, I’ll also share FBBO’s research with American Bird Conservancy and window collisions. Some cool stuff!

This was my second visit to FBBO, and it was just as enjoyable as the first a few years ago. Our area warbler surge seems to be behind a bit (still!), but the lack of warblers this visit did not deter us from having a wonderful time.

We walked numerous bird netting trails, finding them empty as staff bird collectors were ahead of us. The nets are carefully cleared every 40 minutes, putting each bird in it’s own bag, then returning to the banding hut for measurements, fat content rating, age if juvenile/first year, and then receiving it’s band, or record its numbers if already banded.

A female Northern Cardinal getting banded, followed by two photos just before releasement

A few more birds that were banded and released.

Northern Cardinal (male) which actually sang beautifully to us while being held 😊

After I took the above two photos, the FBBO leader was bitten by the cardinal hard enough to draw blood, ouch! Cardinals are the worse for severe bites during banding. Their bite is so strong, Cardinals require steel bands, as they can snap an aluminum band right off their leg.

Gray Catbird

Common Grackle

Red-winged Blackbird (male)

Hermit Thrush

Ovenbird (yay, a warbler!)

Out on our walks, there were at least a dozen Common Yellowthroats (also a warbler) singing their hearts out in the marsh and scrubs.

Common Yellowthroat (male)

And two shorebirds on Foreman’s Branch’s muddy flats.

Solitary Sandpiper

Greater Yellowlegs

Foreman’s Branch

And finally, info and photos of the glass collision testing tunnel and research being performed by FBBO for American Bird Conservancy (ABC).

Windows are among the deadliest threats that migratory birds meet on their journeys, killing up to a billion in the U.S. alone each year. Birds perceive reflections in a glass surface as reality, and when they fly toward a reflected tree or open sky, their mistake is often deadly.

In 2010, ABC began testing and rating glass and other materials to deter bird collisions with their first tunnel, presently in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In March 2022, ABC joined forces with FBBO and Washington College to double its capacity to meet the demands of glass coming from all over the world to be tested.

This testing was absolutely fascinating to see again. In each trial, a just caught and banded bird is released into one end of the 24-foot-long tunnel with video recording the entire flight trial. The bird flies toward the light and ‘blue sky’ at the other end, where two different panes of glass — a test pane and a clear glass pane — present a choice.

It is difficult to tell in the above photo, but there is a soft mist net within the trailer well before the window panes to stop the bird safely from hitting the glass.

Start of a trial above, releasing a bird into the dark tunnel

The tunnel is on a rotating base and is moved often throughout the day to capture the natural sky’s light into the long mirror on each side at the end of the tunnel to mimic lighting effects on the windows.

By studying the birds’ flight paths done by FBBO, ABC is able to assign the glass a Material Threat Factor score based on how many times birds fly toward the test pane; avoidance of the pane indicates that the birds can see and do avoid the glass. Each pane of glass is tested with 80 bird flight trials.

Important note: Tested birds safely bounce off a mist net before reaching the glass, ensuring that no birds are harmed during testing. After a single test flight, each bird is released back into the wild.

I’m hoping you can see a ‘dot’ pattern etched into the above ultraviolet glass pane, a hopeful deterrent to birds that appear to ‘see’ the dots (or some with stripes) and avoid them consistently.

All types of glass is delivered from all over the world for testing

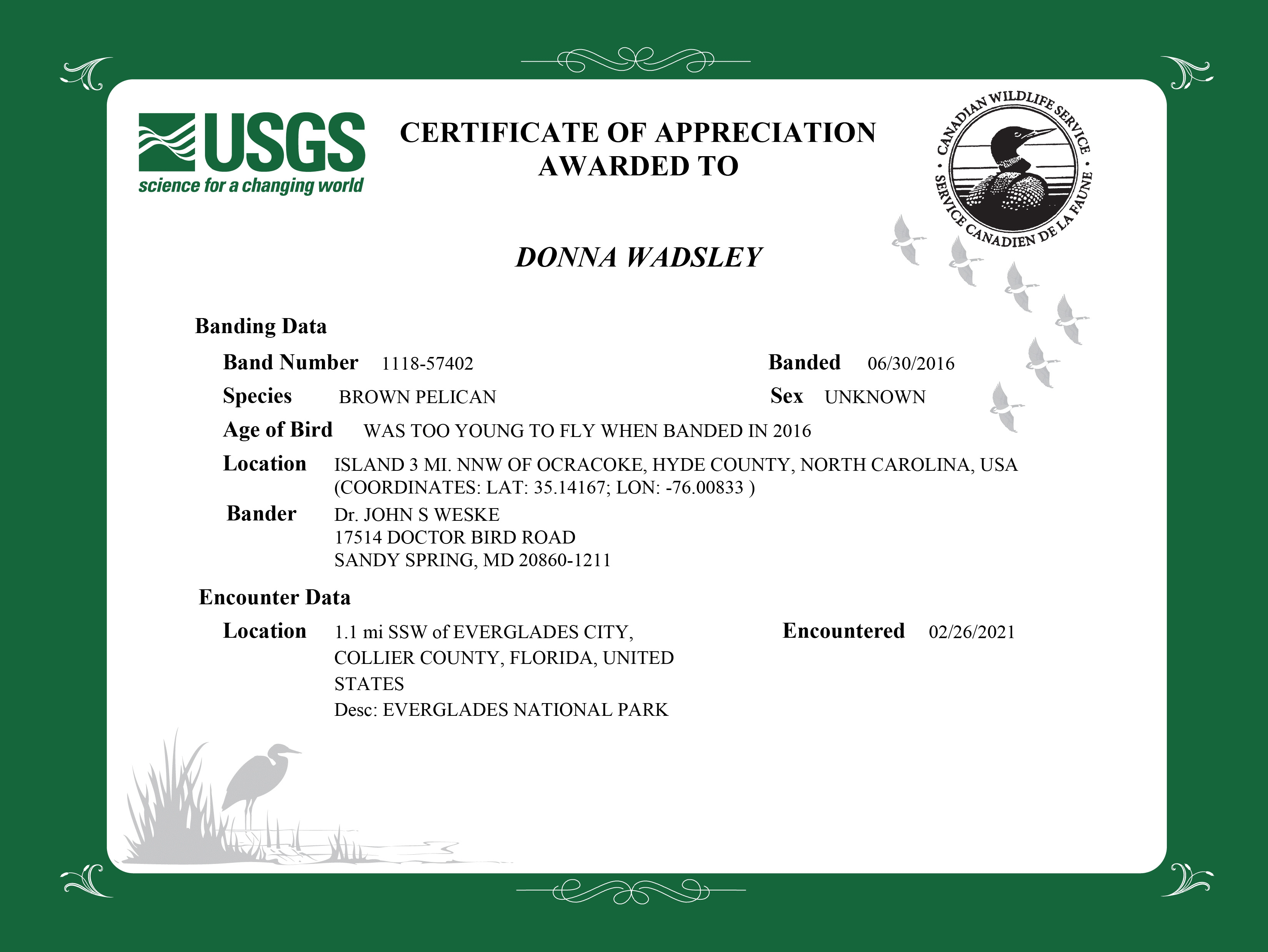

Back to banded birds with a final thought. Encounters with banded birds occur either through trapping a live bird by another banding operation, possibly from a photo, or most often, a recovered band from a dead bird. If you happen to find a bird with a band on it, be sure to report it to Report Band at this link. (reportband.gov) I’ve reported three bands from bird photos I’ve taken, I did not have all the numbers on any, and still two were able to be identified. You even receive a personal certificate with all the known banding details of your banded bird.